|

| Benjamin Eastburn's Map of the Walking Purchase |

Ensconced in the bowels of a poorly-lit dank and musty repository, historical researcher William Joseph Buck was diligently engrossed in a truly noble quest – to fully and properly grasp the curious tale of Pennsylvania’s 1737 Walking Purchase. Like all who venture deep into uncharted archival territory, he too was a man that was seeking the historians’ proverbial Holy Grail, that almost mystical and elusive never-before-seen primary source record that would fortuitously allow for a new and significant insight to valiantly be brought forth with aplomb into a patiently awaiting world.

For

Buck, this night at the archive would either be his coming salvation or yet

another night of bleak frustration, as he was rapidly approaching a monumental

dead end. For all of his stellar work, he was still missing a major piece of

the puzzle, the bow on the package that could that could tie it all together,

that one critical thread running from beginning to end that could serve to

explain it all.

And

then he found it. In a brilliant flash of insight, in a startling EUREKA!

moment, it all became crystal clear.

Buck

had chanced upon a surveyor’s journal entry dated to 1735 that detailed a route

from Wrightstown, the starting point of that famous Walk, to “the Mountain”.

Now it all made sense. Now he seemingly had the proof that scheming Thomas Penn

had orchestrated a secretive “trial walk” well in advance of the actual Walking

Purchase.

Bully

for Buck! The hours of painstaking research had finally paid off… he could now

|

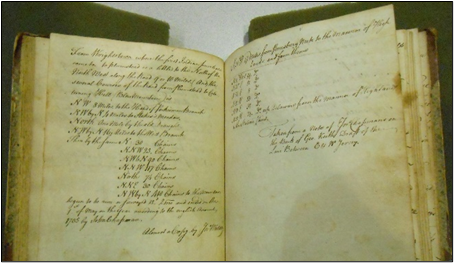

| John Chapman's survey from Wrightstown |

The surveyor's entry:

"From Wrightstown, where the first Indian purchase came to, to Plumstead, is a little to the North of the North West along the Road 9 or 10 miles, and the several Cources of the Road from Plumstead to Catatuning Hills (Blue Mountain) is North West 8 miles to the head of Perkiomen Branch, North West by North 4 miles to Stokes' Meadow, North 1 mile by the old Draught. North North West 16 miles to the West Branch, then by the same North 30 chains, North North West 25 chains. North West 6 chains, North 90 chains, North North West 117 chains, North 74 chains, North North East 30 chains, North West by North 410 chains to the Mountain."

Upon

reviewing this survey, historian Buck ultimately concluded that the course laid

out by surveyor John Chapman took one “to the Lehigh Gap of the Blue

Mountains”.

As

it turns out, Buck was mistaken.

The route from Stokes' Meadow to the Mountain

Instead of passing through the Lehigh Gap, surveyor Chapman’s recorded route takes one through the “Little Gap” just north of Danielsville, PA.

But was this surveyed route, as dutifully noted in Buck’s History of the Indian Walk, actually established to support a trial walk? Or was this doglegged course instead fashioned for some other significant purpose?

A tantalizing clue emerges in the final lines of Chapman’s survey: “Begun to be run or surveyed 22d of 2 Mo. And ended the first of May in the year according to English Account, 1735, by John Chapman.”

68

days. Sixty-eight days, start to finish, to complete a survey that at most

should have consumed no more than a mere two days. Most odd. So, how does one explain this rather

intriguing incongruity?

The

Proprietaries are impatient to know what progress is made in travelling over

the land that is to be settled in the ensuing treaty that is to be held with

the Indians at Pennsbury on the fifth day of next month, and therefore desire

thee, without delay, to send down an account of what has been done in that

affair…

Steel

again picks up the pen some three days later, and this time writes to Sheriff

Smith and to surveyor Chapman:

The Proprietaries are very much concerned that so much time hath been lost before you begun the work recommended so earnestly to you at your leaving Philadelphia, and it being so short before the meeting at Pennsbury, the fifth of the month, that they now desire that upon the return of Joseph Doane, he together with two other persons who can travel well should be immediately sent on foot on the day and half journey, and two others on horse-back to carry necessary provisions for them and to assist them in their return home. The time is now so far spent that not one moment is to be lost; and as soon as they have travelled the day and half journey, the Proprietaries desire that a messenger may be sent to give them account, without delay, how far that day and half travelling will reach up the country.

Clearly, in Steel’s estimation, the survey project underway absolutely needed to be completed forthwith so that certain upcoming deadlines might thereby be met.

Although Steel opted to reference the critically important Pennsbury meeting scheduled for the fifth of May, there was yet another swiftly approaching deadline even more seriously weighing upon the minds of the Pennsylvania proprietors – July 12, 1735, the day that the Penns would formerly announce a “Scheme of a Lottery for one hundred thousand acres of land in the Province of Pennsylvania.”

Therein lies the missing piece of the puzzle: surveyor Chapman’s days had been engaged in the business of mapping out a large quantity of parcels destined for the future lucky land lottery winners.

Thus, this particular

route had been designed not in anticipation of the formal day and a half’s Walk

(still some two and a half years hence) – there had already been another route

laid out for that given purpose – instead, this course had been established solely

to direct the providentially blessed jackpot winners from the county seat up to

their newly acquired land holdings deep within the wilderness of Penn’s Woods.

So, if this wasn’t the

route of the “Trial Walk” that preceded the Walking Purchase, then where does

one find the actual trial walk route?

But before we peel back

the curtain to reveal that which has been right in front of our nose for all of

these years, let’s first consider a corroborating testimonial regarding the route

of the trial walk as proffered by Sheriff Smith:

And this Affirmant further saith he being employ’d in ye May proceeding at a going said Walk to get some Persons to try said Course by a Straight Line as near it could, he accordingly decided with some six other persons try of proposed course by as near a straight line as they could, but in loading them over Mountains, at times, a very rocky broken way in going there…

Sheriff Timothy Smith's examination deposition

At the very least, Smith’s testimony reveals that the assigned objective of the May walk was to follow a straight-line course to the greatest degree possible. Further, that straight-line course – not a doglegged course – took them into the mountains.

Let’s now have a look at John

Chapman’s map:

John Chapman's Walking Purchase map

Chapman’s map presents

what at first glance appears to be an extraneous uncaptioned line. The line

follows a by-the-compass true-North bearing extending from the westernmost

point of the Neshaminy Creek up through the Kittatinny Hills and then into the

Blue Mountains.

One can safely assume

that cartographers, with their penchant for detail and accuracy, would not be

rendering extraneous lines on their maps unless such a depiction was a

necessary and integral part of the overall story to be told – hence, this particular

line on John Chapman’s map represented the cartographer’s almost surreptitious effort

to also depict the straight-line course of the original trial walk.

Were one to extend a

right angle from the end-point of this line toward the Delaware River, one can

see that it would thereby serve to capture the Minisink territory wherein the

Dutch from New York’s Ulster County had recently settled (in rather close

proximity to Nicholas Depue’s Indian trading post at Shawnee-on-Delaware).

Nicholas Depue's tract: PHMC Survey #D86-284

Naturally, one would want

to know why the straight-line trial walk shown on Chapman’s map didn’t became

the route ultimately taken in the 1737 Walking Purchase transit. Sheriff Timothy Smith offers an explanation:

"at

times, a very rocky broken way in going there which they assumed and conceived

could not answer, Affirmant therefore advised ye Walk they should keep of said

Road & old Paths as much as might be."

Sheriff Smith, “employ’d

to superintend” the Walk had made a judgment call. The straight-line route that he had

previously traversed with six men would not be utilized for the subsequent

Walking Purchase owing to rocky terrain considerations; instead, roads and

paths would be followed.

As the suitably marked and blazed northward trail that led up to the tracts of the 1735 Pennsylvania Land Lottery scheme was the clear and self-evident alternative choice as the optimum northerly path to follow, Chapman’s surveyed route, by dint of Smith’s decision, would therefore become the final course eventually taken on the 1737 Walking Purchase.

One can see that the route of the Purchase journey, as illustrated on John Chapman’s map, is virtually identical to the route surveyed by Chapman in 1735… with one glaring major difference: the final end-point of the Walk. Chapman had originally surveyed a route that passed through the Little Gap. In his later Walking Purchase map, however, the primary route thereon is depicted as approaching the Lehigh Gap.

So, which route was really taken?

The answer comes to us

from the very lips of none other than the triumphant Walking Purchase victor,

the acclaimed Edward Marshall. But

first, let’s establish some necessary background.

The Walking Purchase was

performed in three 6-hour segments. The

three walkers, Solomon Jennings, James Yeates and Edward Marshall, began their

Walk “at Six a Clock in the morning of the said Twelfth Day of September from a

Chesnut Tree in the Land of John Chapman, in Wrights Town.”

By noon they had arrived

at Stokes’ Meadow, referred to in Sheriff Smith’s testimony as the “Plantation

of Widow Wilson where they halted and dined.”

They continued “till

fifteen minutes past Six a Clock in this evening when they halted near an Indian

Town called Hockyondockquah, and there stayed all night;”

Thanks to the 1735 survey

efforts of Nicholas Scull, the location of this cited Indian Town may now quite

readily be ascertained:

The Hokendauqua Indian Town. PHMC Survey #D89-232

Nestled between the West

Branch of the Delaware River and the Hokendauqua Creek, the site of this Indian

Town becomes a vital part of our story.

Edward Marshall explains

in his own words:

"That

the next morning some of the Company’s Horses being strayed away they spent

about two hours in looking; they began their Walk again (without any Indians

with them at Eight a Clock from the said Station or place where they left off,

they then continued their Walk through the Woods, about the said Course of

North North West by a Compass."

In all of the testimonies

provided by the Walking Purchase participants, this is the one and only time

that a specific compass bearing has ever been cited. As such, it is significant. Upon departing from their

overnight camp next to the Indian Town, the walkers used a compass and decided

to head in a North North West direction.

Such a choice of

direction would lead them not through the Lehigh Gap and up to the Jim Thorpe

area; rather, they would instead pass through the “Little Gap” and ultimately arrive

at their mountaintop destination.

And now, the

million-dollar question: “If this is what the first-hand primary source

testimony tells us, then why do all three of the Walking Purchase maps (Chapman,

Evans, and Eastburn), all show the Walk’s route as directed toward the Lehigh

Gap?

What sinister machinations are at play?

We get our first clue that something is seriously awry upon reviewing the historic Walking Purchase deed itself – a deed that is shockingly missing two of its most critical words, the Walk’s directional indicators.

That blanks existed in

the document was a fact well known to analysts after the conclusion of the

French and Indian War. They, however,

were of the view that an empty space had deliberately been set aside for the

direction of the route; they did not suspect an alternate possibility – that

the directional indicators, once written, had later been expunged. Their commentary:

it

now remained to draw the Line from the End of the Walk to the River Delaware.

We have seen above there was a Blank left for the Course of this Line: Taking

the Advantage, thereof, of this Blank, instead of running by the nearest Course

to the River, or by an East South-Course, which would have been parallel to the

Line from which they set out, they ran by a North-East Course for above an

hundred Miles across the Country to near the Creek Lechawachsein, and took in

the best of the Land in the Forks, all the Minisinks, &c. Thus a Pretense

was gained for claiming the Land in the Forks without paying any Thing for it.

On what basis then does

one arrive at the conclusion that spoilation had occurred, that words in an

official document had actually been deliberately erased?

Scrutinizing the areas of

text within the parchment, one notices that the scribes of the period had

produced an eighteenth-century equivalent to modern-day college ruled paper –

there are very fine faint straight lines underneath all of the hand scripted

words in the document… except for two. There are no such guiding lines beneath

the empty/blank spaces in this deed (seemingly sufficient proof of the not-so-careful

expungement of previously written words).

The erasure revealed. High resolution image provided courtesy of the Pennsylvania Archives.

As such, the blanks in

the Walking Purchase Deed illustrate what one would call an initial “intent to

deceive,” an intent that never blossomed into its full fruition. Had the deception been rigorously pursued to

its logical conclusion, the blanks would have been filled with a replacement

set of alternate directional indicators.

But apparently, someone

had some second thoughts…

While time could likely

be profitably spent narrowing down the field of suspects to those that had

documentary access, individuals such as James Logan, chief steward of the

Pennsylvania Land Office, the man who would certainly have had direct access to

the Walking Purchase deed, the man who had hired the three Walking Purchase

walkers, the man who as one of Pennsylvania’s largest land speculators was

actively selling land never purchased from the Indians, it would not be fitting,

at this point, to level such serious charges at men like Logan without the

benefit of further corroborating evidence.

It is sufficient for now

that the finger of suspicion can be found pointing directly toward the Pennsylvania

Land Office.

What remains clear, however,

beyond a shadow of a doubt, is that some given party was perfectly willing to

either erase or manipulate the historical record to further their own ends. Thus,

we find ourselves with a classic whodunnit requiring investigation.

In such cases, one always

begins by assessing the credibility of the witnesses in the drama at hand.

On the one hand, we have

Edward Marshall who on March 1, 1757 – almost twenty years after the Walking

Purchase – recalls an exceedingly specific compass bearing used upon departure

from the Hokendauqua Indian Town (that would have taken the party of walkers directly

through the Little Gap).

On the other hand, we

have the maps produced by the Pennsylvania Land Office surveyors, Lewis Evans,

John Chapman and Benjamin Eastburn, all three of which suggest a crossing point

at the Lehigh Gap.

So, who do we believe?

If we believe Marshall,

then we must presume a wide-ranging conspiracy within the walls of the Land

Office.

If we believe the

cartographers, then Edward Marshall must have been unfortunately mistaken in

his specific recollection.

How do we get at the

truth?

As all three Walking

Purchase maps are practically identical, it boils down to the remaining written

testimonies of the other Walking Purchase participants. If they concur with the maps’ route details,

then Marshall must have been in error.

If their commentary

doesn’t fully concur with the cartographic elements presented, then a vast conspiracy

has indeed come to light.

The endpoint of the Walking Purchase depicted

Looking at the geographic

elements along the walkers’ route, one quickly concludes that a great number of

waterways were crossed, with some, such as the Aquashicola Creek being rather

wide.

We’ll investigate which waterways are actually mentioned by the Walk participants in the effort to determine whether the route depicted was actually the route taken.

Do the testifying walkers actually reference crossing the Aquashicola? We’ll see.

At the start of the walk,

participant John Hyder (who proposed to be one of the walkers), mentions that

their starting point was “about four miles from the River Delaware.”

The next waterway,

mentioned by Marshall, Smith and Alexander Brown (a witness to the Walk who

went “out of Curiosity”), was the Gallows Hill run.

Brown claims that he came

“about half of a mile under Gallows Hill,” while Smith merely attests to coming

near it.

Both Hyder and Ephraim

Goodwin (another participant who also joined “out of curiosity”), reference the

Tohickon Creek; Hyder asserting that they kept to the Durham Road “till they

came about Five or Six Miles beyond Tohiccon,” while Goodwin merely mentions

passing over it.

On the route to the widow

Wilson’s plantation, not a single participant – not one – mentions crossing or

passing the Saucon Creek (although it’s quite clearly represented as a crossing

point on the maps). Neither is the

Menacasy Creek mentioned.

|

| The Saucon and Monacasy Creeks |

Ephraim Goodwin and

Edward Marshall both allude to Cooks Creek near the widow Wilson’s plantation.

Walk participant Thomas

Furniss mentions reaching Durham Creek, and five of the walkers all report

crossing the West Branch of the Delaware “commonly called Lehigh.”

Ephraim Goodwin next

reports “passing over Mill Creek called Hockyoudoky near where Hugh Wilson’s

Mill is since erected.”

All participants report

stopping near the Indian Town in the Forks.

No participants at all

report crossing the Aquashicola creek.

Marshall references “the

said Yeates having given out and stopped at Tobyhanah Creek.”

Alexander Brown mentions

the East Branch of the Pocopohcung, and finally mentions crossing “a large

brook.”

In the aggregate, one

notices that a rather large number of smaller creeks and runs are being cited within

these walker testimonials, while certain key waterways that purportedly were

crossed (if you’re prone to believing the cartographers’ representations), such

as the Saucon Creek near Bethlehem and the Aquashicola, don’t even receive a

passing mention by anyone. The

situation is such that it creates a rather sizable element of doubt.

Ultimately, you, the

reader, are to be the jury in this contentious matter.

So, are the witness

statements credible? Have you developed any

gnawing suspicions?

Perhaps what is needed to

resolve the growing doubt in this case is a brutally thorough cross-examination

of one of the cartographers.

As we’ve heard from the

Walking Purchase witnesses, it only seems fitting to next call upon a

cartographer to similarly testify.

Allowing the cartographers’ work product to speak on their behalf, we take note of a second uncaptioned extraneous line that almost inexplicably appears upon this map.

It appears to be Chapman’s surveyed route from the Hokendauqua Indian Town on a North-North-West bearing to the actual endpoint of the Walking Purchase as earlier stipulated by Edward Marshall.

Again, the cartographer

would only have added this line if it was integral to the story of the Walking

Purchase that he was attempting to convey.

A hidden message, perhaps.

As walker witness

testimonials don’t appear to wholly corroborate the cartographic

representations, and as the appearance of uncaptioned extraneous lines in at

least one of the maps seems to point to some underlying degree of discord

within the surveyors’ ranks, the conclusion is therefore reached by this

researcher that Edward Marshall must have been correct in his recollection, and

that a conspiracy to deliberately change and relocate the endpoint of the Walk

must have been afoot within the Pennsylvania Land Office.

An explanation for such nefarious

behavior is now upon the docket.

Lewis Evans' map of the Walking Purchase

While the 1737

Pennsylvania Walking Purchase on its own merits served to secure the territory

known as the Forks of the Delaware, and while the line to the Delaware River

from the true endpoint of the Walk succeeded in safeguarding the interests of

Nicholas Depue and his fellow Dutch settlers that resided in proximity to

Shawnee-on-Delaware, the remaining vast stretch of territory in the Minisinks

that extended up to the Lackawaxen River would not have been covered by the

agreement as originally formulated.

In fact, one can spot no

Lenape Minisink Indians as signatories to the Walking Purchase deed. The names of Lapowinzo, Nutimus, Sassoonan

and other prominent Delaware Indians are there – but no Minisink chiefs opted

to leave their respective signatory marks upon the document.

Although it would strike

one as axiomatic that one cannot purchase land that is not up for sale, the

Penn’s agent, William Allen, apparently had a decidedly different set of views

on this given topic. He had been selling land up and down the Delaware River

without regard to the payment of a single shilling to the native land owners.

Allen claimed rights to

properties situated all the way up to the confluence of the Lackawaxen and the

Delaware, and Land Office officials were certainly well aware of who was

buttering their bread.

A decision was therefore

reached to protect William Allen’s interests.

The endpoint of the Walk

would be shifted to a more propitious location, Allen’s properties would thereby

be completely encompassed, and no one would be the wiser… or so they thought.

But they all had forgotten

about Captain Harrison.

The walkers on this

historic journey took note of the fact that the Walk ultimately terminated near

the site of an Indian Town named Pocopohcungh, where “a noted Indian call’d

Captain Harrison then lived.”

The significance of this particular observation should not escape us. The noted Captain Harrison was, in fact, Delaware Indian War Chief Teedyuscung’s very own brother, a key witness to the final moments and actual endpoint location of the 1737 Walking Purchase.

Historians are aware of

this family relationship owing to a letter penned during the period of the

French & Indian War by Northampton County’s Captain Jacob Orndt to Major

William Parsons that identified the status of these two Delaware Indian

notables as siblings.

Chief Teedyuscung would eventually

put forth the claim that “This very ground I Stand on was our land &

Inheritance, and is taken from me, by Fraud.”

In due course, the Chief would come to wreak unbridled havoc upon the

Northampton County backcountry.

As a result of the

arrogant greed and deceit displayed vis-à-vis the Walking Purchase of 1737, the

surrounding area would in time come to reap the whirlwind.